The Valdez School for Wayward Girls

The first-ever all-women heli-skiing camp in Alaska’s central Chugach Range attracted a motley crew of diehard skiers. Valdez may never be the same.

With the Alaskan sun still burning at 8 p.m., soft-spoken Karen, an actuary who works on retirement plans, assessing financial risk and calculating pensions, climbs up POS (piece of sh–), a 30-foot-high vertical ice cube, with great care. She swings the ax-pink. It hangs precariously in the ice. Pink. “This is an angry woman’s sport,” Kristen Ulmer yells up. “Get mad with that thing.” She pinks a little harder, inching her way to the top. Clearly, ice climbing is a sport that mirrors an individual’s approach to life. Next up the ice, Kim, whose arms are as burly as the exhaust pipes on her Harley, swings the ax–Ah-yaaah!! The ax lodges solidly into the ice. Ah-yaaah!! She is up and down in minutes, spent but thrilled. “I was one whacking motherf–er up there!” she laughs.

With the Alaskan sun still burning at 8 p.m., soft-spoken Karen, an actuary who works on retirement plans, assessing financial risk and calculating pensions, climbs up POS (piece of sh–), a 30-foot-high vertical ice cube, with great care. She swings the ax-pink. It hangs precariously in the ice. Pink. “This is an angry woman’s sport,” Kristen Ulmer yells up. “Get mad with that thing.” She pinks a little harder, inching her way to the top. Clearly, ice climbing is a sport that mirrors an individual’s approach to life. Next up the ice, Kim, whose arms are as burly as the exhaust pipes on her Harley, swings the ax–Ah-yaaah!! The ax lodges solidly into the ice. Ah-yaaah!! She is up and down in minutes, spent but thrilled. “I was one whacking motherf–er up there!” she laughs.

Welcome to H20 Heli-Guides’ Women Ski Alaska Big Mountain Camp. The brochure promised a week of heli-skiing, avalanche training, crevasse rescue, ice-ax self-arrest, rope work, ice climbing, and “bonding with like-minded women.” Female bonding, it seems, is the inevitable ingredient. It’s been the common denominator of the touchy-feely, wine-and-cheese affairs that have defined traditional women’s clinics in the past decade. But this is Alaska. This is the Chugach. Where the mountain faces are as big as 10 football fields stacked on end, tilted to 50 or 60 degrees and rippled with flutes. A 100-foot cliff to the right, a couple crevasses to the left, and a gaping bergschrund below you. Have a nice run, sister.

The Chugach camp is one of a handful of programs cropping up across North America that represent a new paradigm in women’s clinics. Forget the seaweed wrap and the chocolate on your pillow: These camps are about strapping on a harness and tackling jaw-clenching steeps, jumping cornices and cliffs. The campers attending are the first generation of desk jockeys out to rip big mountains-and do it as hard as the guys do.

Aside from the terrain, the camp’s big draw is the chance to get one-on-one coaching from a squad of elite female skiers: Alison Gannett, Wendy Fisher and Kristen Ulmer. Of course, these are sponsored athletes who we naturally associate with Valdez. The campers, on the other hand, are women with nine-to-five jobs and families.

Kim, 39, is a chemical engineer from Vancouver, Washington, who plays ice hockey and skis at Mount Hood. She’s snowboarding on this trip because her knee is still tender from a moose attack. There’s also Karen, 38, the actuary from San Francisco, who talks in a sweet little squeak; Christine, a French lacrosse mom from Long Island, celebrating her 40th; Tricia, 30, a bartender from Big Sky; and me, a 36-year-old editor from Boulder, who, after editing a story by Kristen Ulmer on the dangers of the Chugach, once vowed never to ski Alaska. In sum, the campers are all adventure-seekers ready to take on the biggest terrain of the ski world.

Kim, 39, is a chemical engineer from Vancouver, Washington, who plays ice hockey and skis at Mount Hood. She’s snowboarding on this trip because her knee is still tender from a moose attack. There’s also Karen, 38, the actuary from San Francisco, who talks in a sweet little squeak; Christine, a French lacrosse mom from Long Island, celebrating her 40th; Tricia, 30, a bartender from Big Sky; and me, a 36-year-old editor from Boulder, who, after editing a story by Kristen Ulmer on the dangers of the Chugach, once vowed never to ski Alaska. In sum, the campers are all adventure-seekers ready to take on the biggest terrain of the ski world.

Hilaree Nelson, a mountaineer from Telluride and one of the guides for the week, kneels over a white plastic mat marked with a series of black flux lines, explaining how an avalanche transceiver works. Nelson is a woman of great contradiction. She’s the girl next door who mounts ski expeditions to Mongolia. She is runway-model gorgeous, yet she eschews makeup and chews tobacco. The campers are in awe.

We practice finding beacons in the slush-covered parking lot, then move on to tying knots. Prusiks, münters, girth hitches. Ulmer shares her secret for the figure-8 follow through: “To get the right length, I hold the rope from my nipple out to here.” Next, Nelson runs through a crevasse rescue and shows how to set a T-anchor with a pair of skis. If there are more down days, the plan is to plunk a camper into a crevasse and rescue her. Karen whispers conspiratorially, “I can’t wait to get into one of those crevices.”

What the rest of us can’t wait for is to ski powder, the plan that night at Fung Ku, the local sushi joint, is to “drink it blue,” as they say in AK. Meaning, drink enough sake and Sapporo, and the clouds will dissipate. A group of guys at the next table sends over a couple bottles of warm sake. Gannett isn’t surprised: “I’ll be here for a month, and I’ll be the only girl except for the waitresses at the Totem.” Somewhere between spicy tuna rolls and moo goo gai pan, the conversation turns to vibrators. As if explaining the correct technique for tying a münter hitch, Gannett expounds the virtues of The Bunny, a must-have electrical accouterment in any girl’s nightstand. “You see, it’s got these little ears…”

The sake worked. The next morning, the soup clears out, and the group is packed into a minivan-sized snow pit with Mark Kozak, a six-foot, two-inch avy god with an Ultra Bright smile and a voice that is one part butter, two parts Barry White. With eight feet of snow in the last week, we are up in the mountains spending the day learning about avalanches instead of getting caught in them. He fills our heads with snow-safety info: the good karma of two stellar snowflakes sintering and the bad ju-ju of temperature gradient. Of stress and strain, failure and fracture.

To determine the stability of the snowpack, Kozak lightly punches the snow with his fist, moves it down an inch, and punches again. “It’s the hand hardness test,” he says. A wave of giggles ripples through the pit. He starts to discuss how the “level of penetration…” More giggles. “It’s better if it goes from soft to hard…” At this point, campers are falling down laughing. Kozak turns red.

After some degree of decorum returns to the pit, we measure the slope angle, study snow crystals in a magnifying loop, and do a Rutschblock test: Kozak steps onto the six-by-five-foot block of snow we’ve cut out, and it spits out like a banana from a peel on the first jump, shearing cleanly 90 centimeters down. Yikes. Picking our way carefully down the high point on the ridge, we ski through snow that billows up around our armpits, snow we now understand is out to bury us alive.

The next day, with gravity and a little solar heating, the snowflakes have sintered enough that we can ski. But it’s still dicey, so we stick to mellow terrain, which, by AK standards, means 30- to 35-degree pitches, gullies, and ridges. The slopes could still slide, but at least there are no cliffs or crevasses or super steeps to worry about. The campers watch slack-jawed as athletes they’ve only seen on the big screen ski down in front of them. Gannett slices wide turns through the deep snow, every arc strong and smooth. Her approach is scientific: A ski route is a problem that she analyzes and solves. With a ski-racing pedigree, Fisher machs down every pitch as if it were the Hahnenkamm. Ulmer’s style is more mugger-meets-millionaire-in-dark-alley: She attacks everything.

The next day, with gravity and a little solar heating, the snowflakes have sintered enough that we can ski. But it’s still dicey, so we stick to mellow terrain, which, by AK standards, means 30- to 35-degree pitches, gullies, and ridges. The slopes could still slide, but at least there are no cliffs or crevasses or super steeps to worry about. The campers watch slack-jawed as athletes they’ve only seen on the big screen ski down in front of them. Gannett slices wide turns through the deep snow, every arc strong and smooth. Her approach is scientific: A ski route is a problem that she analyzes and solves. With a ski-racing pedigree, Fisher machs down every pitch as if it were the Hahnenkamm. Ulmer’s style is more mugger-meets-millionaire-in-dark-alley: She attacks everything.

Huddled on the glacier, waiting for a pick up, we can feel the thump, thump of the A-Star’s rotors all the way down to our footbeds. The heli rockets us at 150 miles per hour toward 2,000 feet of sheer rock, then, with a subtle shift of the stick, the pilot lifts the bird over a knife-edge ridge, and the world drops away again. Our stomachs drop with it.

The pilot banks hard, heading back toward the thin crown of granite to a seemingly impossible landing. He sets us down on a little postage stamp of snow, and we crawl out and crouch in the 11 o’clock spot in front of the heli, a cliff just feet behind us. The pilot dive-bombs, and the heli plummets out of view. It’s amazing every time.

In the afternoon, our guide, a quiet redhead named Bill McCabe, takes us to The Island. Wortmanns Glacier wraps around this massive hunk of mountain in a great frozen squeeze before oozing down the valley like the tongue of some enormous albino snow giant. The heli drops us in the landing zone, or LZ as we learn to call it, and he leads us to a dogleg chute with a 50-degree entrance. “It’s cliffs to the right, and the slough will collect in the runnel on the left,” McCabe says. This time the loud thump, thump is the sound of my heart. Ulmer skis it first, then me, and between us, we knock off an eight-inch slab of slough.

Christine, the lacrosse mom, is next. She decides to sidestep into the couloir, but the farther she goes, the more difficult it becomes even to move. Ten agonizing minutes into it, and only a third of the way down, she is officially gripped. Gannett skis in to talk her down. “Try counting steps,” she encourages. “Just get to 10.” Gannett promises, “it’s not high consequence,” meaning if she did fall, she’d likely just tumble a thousand feet, maybe tear a knee. Nobody’s dying today. But the concept of consequence is relative. Christine is thinking about her eight-year-old daughter’s birthday party on Friday. She doesn’t want to tear anything. Gannett starts singing, “You put one foot in front of the other.” It works. Half an hour later, Christine reaches the apron below the couloir and skis to the bottom, legs quivering. Though her attitude is good–”Hey, nobody walks down a thousand feet like I do”–the run proves to be mental baggage she’ll drag around for the rest of the camp. A few days later, Christine, who had planned to leave early from the get-go, would turn to me and say, “I don’t think I’m coming back here.” She was relieved when the time came to leave. But months afterward, she told me the experience gave her a new confidence.

While we wait for the heli in the pickup zone (a.k.a. PZ), Ulmer entertains with cartwheels and headstands. “What other things would you consider impossible in a snowpit?” Somebody suggests something lewd, and Ulmer jumps McCabe. He turns red. “I have maybe four female clients all year,” he says. “I haven’t seen this many women in a long time.”

At the bottom of another run, McCabe buries his pack with a transmitting beacon inside. It’s time to practice what Nelson taught us in the parking lot. While we wait, Karen gives Fisher and Ulmer retirement advice-”compound interest, Roth IRAs, stocks, life insurance….” They are as rapt as Karen was during their avalanche stories. Then this bookish, demure thing shows us the belly button ring she got during a library break with her actuary buddies. “It makes me feel sexy.” And she’s going to get an armband tattoo, she tells us, once she finds the right design.

When McCabe’s ready, Fisher sets up a hypothetical scenario. “Okay, the slide is 30 meters wide, skier last seen here.” The clock starts ticking. Karen, who has been practicing her avalanche swimming in bed at night, goes first. Beep, beep, beep. The beacon homes in on the pack, but Karen has lost valuable time fumbling with her shovel. She casts the deconstructed probe like a fishing rod, cinches up the metal pieces, and starts probing the snow in an outward spiral. Thunk, the probe hits home on the third jab, and she starts digging. But it’s taking too long, she thinks, starting to panic slightly. The pack can’t breathe! Finally it pulls loose. She saves the pack in less than five minutes.

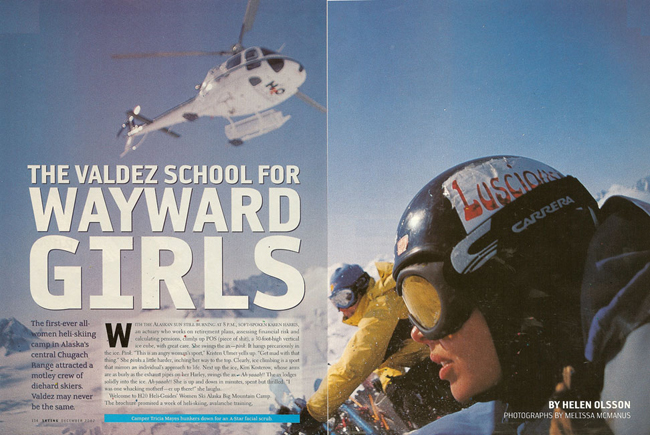

A long-blond-haired snowboarder from Big Sky, Montana, with a Ride it Sister patch on her pack, a Luscious sticker on her helmet, and duct tape on her mittens, Tricia is staring wide-eyed out the heli window. Peaks crush into the horizon like crumpled origami, and seracs sparkle like heaps of broken glass. The pilot works the bird back and forth to lodge the skids into a razor edge of snow. The landing puts us at the top of a narrow 45-degree ramp with a big mother of a cliff to our left and a rock wall to our right. It’s never been skied.

A bartender who once lived in a van, Tricia had been boarding the world from Slovakia to Switzerland before arriving in Alaska. “I make lots of money in a short time,” she says. She figures half her $8,000 yearly salary went to this trip. Though the finances seem a little fuzzy, she is, in Christine’s words, “living the dream.” She’d seen an ad for the trip but hesitated. Then in an airport bar, a 60-year-old man convinced her to go for it. “He told me, ‘You don’t want to get my age and have regrets.’ So, I put down my beer, headed for a pay phone, and made the reservation.”

Tricia goes first, carving big turns, shooting rooster tails in the air, and outrunning her slough. She boards it like a pro. No one in the group does as well; I get taken out by my own slough, and Kim catches an edge and cartwheels down, scaring the guides. “That was awesome, you ripped it,” Ulmer tells Tricia at the bottom. “Did I? Man, if Kristen Ulmer says I ripped it…wow,” Tricia bubbles. Her trip is made. She will have no regrets. Because it’s a first descent, we get to name it. We decide on “Girl Spot”-G-spot for short. McCabe turns red.

In the PZ, Gannett puts a finger to the side of her nose and gives an authoritative blow. Fisher lets out a huge belch. Kim pulls a Fem Funnel from her pack, and walks off, talking about writing her name in the snow. “I’ve never seen anything like that,” McCabe says. “Where do you get those?” “Peelikeaguy.com,” I say. He turns red. Suddenly we hear a roar as a slide comes cascading over a nearby rock band. It silences the group for the first time in a week.

On our last day, Nelson and McCabe decide to crank it up. Turner’s Tomahawk is a 3,000-foot fluted face that’s 50 degrees at the top, dotted with rollovers, and has a huge bergschrund at the bottom. My biggest fear coming to Alaska was the bergschrund, where vertical face meets glacier, and the glacier peels back under its own enormous weight, leaving a crack in the snow as deep as several hundred feet.

McCabe tells us to watch for the tracks and a stick in the snow that indicate a snow bridge where we can safely cross. Ulmer, Gannett, and Fisher ski the flutes. Karen heads skier’s right to a wide-open, untracked powder field. By now, her quads have gotten stronger and she nails it. Tricia floats down a gully, and Kim follows the coaches down the flutes.

I’m up. In the heavy snow, every turn feels like doing a 200-pound leg press, but the run is pure elevator-shaft exhilaration. By the time I get to the bottom, though, the tracks go every which way. They are an indication of nothing. Suddenly I see the stick. “Point ‘em,” I think. I straight-line it for about 25 feet, when, in my peripheral vision, I see another stick way off to my left. Oh shit. I feel like Wile E. Coyote suspended in the air, about to plummet thousands of feet. And I do plummet, about 25 feet, over the biggest part of the bergschrund. I clear the icy death trap but explode on the other side. Poof. Just like the coyote. I double eject and do several ass-over-teakettle rotations. I now have an acute understanding of why they call this run Turner’s Tomahawk. I am the Tomahawk.

Over dinner at the pipeline club, the dismal, smoky restaurant-bar-poolhall where Captain Hazelwood slurped back vodka doubles before ramming the Exxon Valdez into Bligh Reef, Gannett and Fisher turn the group on to Creamsicles (vanilla Stoli, ginger ale, and OJ). As we sip our drinks and devour big steaks, the group counsels Tricia, who’s having trouble with her cheating, no-good rat of a boyfriend. “I don’t know what I’m doing,” she says in exasperation. Gannett tells her, “Dump the chump.” We all nod. It hits me then that, although this camp was about ripping near-vertical slabs of snow, managing slough, tying knots, and learning to fend for yourself in big mountains, the campers and coaches have, dare I say it, bonded.

In fact, this seminal group of Valdez women has narrowed the gap between pro skier and weekend warrior. In the PZ at the bottom of Turner’s, I found Karen hugging and consoling Ulmer, who thought she might have torn her knee in a weird turn on the flutes. “I’m wiggin’!” Ulmer said, in tears, “I am wiggin’!” The mentor-prodigy roles had suddenly been reversed. It was a testament to the power of this camp that a student could become the teacher’s rock.

Over pool and beers, Karen, a great contradiction in her new Carhartts and old Gucci sunglasses, borrows a pinch of Nelson’s Skoal. When she gets home, she says, she’s buying her own beacon, shovel , and probe–and getting that tattoo for sure.

This article first appeared in Skiing Magazine in December 2002.