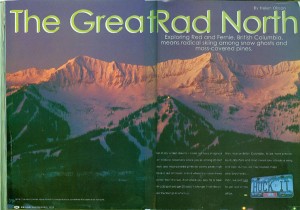

Exploring Red and Fernie, British Columbia means radical skiing among snow ghosts and moss-covered pines.

Even in my wildest dreams I could not have imagined such a place. Mountains where you ski among 20-foot ghosts and moss-covered pines on downy peaks high above a sea of clouds. A land where the moon shines brighter than the sun. And where you pay for a beer with a 20 spot and get 20 back in change. I had discovered the Shangri-la of schuss.

Well, interior British Columbia, to be more precise. My buddy Pam and I had heard tales of radical skiing and epic dumps, we had studied maps and brochures… man, we just had to get out of the office.

Driving north from Spokane, Washington, we pass a sign outside a snowblower shop: “Snow: The World’s Most Annoying Commodity.” This, I decide, is a bad omen. Then, at the Canadian border, we are interrogated by Dudley DoWrong (it occurs to me that maybe, just maybe, I should have brought my passport). “And the nature of your visit to British Columbia?” he probes. When we admit to covert skiing operations, his snakelike eye-slits open wide, his grimace erupts into a grin, and he bursts forth conspiratorially: “It has been dumping!! The skiing is awesome.” With that he waves us into Canada.

The parking lot of the Ram’s Head Inn, the only lodging at the base of Red Mountain, is filled with copious amounts of the world’s most annoying commodity. A very good omen. The snowbanks are piled so high, the entire first floor is buried. But when Pam and I venture out to ski the next day, we’re disappointed to see that we can see very little. The mountain is wedged in a dense fog.

Red overlooks the Columbia River Trench, a valley system of winding rivers and big lakes. All that moisture means the skies are often gray and foggy. But nobody minds when there’s powder. And that happens when a low-pressure storm system spins out of the Gulf of Alaska, wrings out some moisture over the Coastal Range, and dumps the light and fluffy on Red.

Red overlooks the Columbia River Trench, a valley system of winding rivers and big lakes. All that moisture means the skies are often gray and foggy. But nobody minds when there’s powder. And that happens when a low-pressure storm system spins out of the Gulf of Alaska, wrings out some moisture over the Coastal Range, and dumps the light and fluffy on Red.

On the chair, we meet Max Bankes, a former property-tax assessor dressed in a grubby and tattered black-and-yellow North Face one-piece. He’s become a rental-shop guy, landscaper, and construction worker so he can ski every day. We pretend to be ignorant Americans, and Max agrees to give us a tour.

Red Mountain is actually two mountains, Red and Granite. First we take a creaky double to the top of Red and cruise around the mountain’s flank. The fog lifts just high enough that we get pretty views of the town of Rossland nestled below. But Granite Mountain, where a hundred unmarked trails wrap 360 degrees around an ancient volcano, is where we want to be. On the chair, we can’t see much, really, but Max assures us, “To the left, it’s pretty much black to double black, and to the right…well, it’s pretty much black to double black.” The summit is covered with 20-foot-high forms snow-caked beyond recognition. Only a tiny tuft of green pine poking through the thick white crust gives them away as trees.

We work our way around the massive granite cone, skiing long runs through the mist on open powder fields, through thick glades, and down steep avalanche slide paths. Pam keeps getting vertigo, and has to stop and make sure the ground is underneath her. I tell myself that vision is a crutch and ski by braille, my feet reading the terrain. Every run is unique, but each leaves us with the same sensation: We are skiing raw mountain. The terrain rolls and heaves underneath us as if it were alive. There are bumps and cliffbands and boulder fields and rock gardens and ridges and trees. Lots of trees. It’s like tumbling down a series of ledges. And the runs are so long¿more than 2,000 vertical feet–our ears pop at the bottom.

Mount Roberts, the peak to the southeast of Granite, is covered with north-facing, avalanche-prone chutes crowned by a 15-foot cornice. I get the willies just looking at it. It’s out-of-bounds terrain, but legal; here there are no police and no gates. We don’t have beacons or shovels, so we don’t hike to the top. Plus, Mahas promised us freshies along Roberts’ gladed shoulder.

All around us tall, skinny pines reach for the sky. With branches sagging under heavy snow, they look like gigantic closed umbrellas. Like the trees in a Dr. Seuss landscape. Moss hangs from the trees in shades of green and black witch’s hair and old man’s beard, the locals call it. I remind myself I am in Canada, not a Louisiana swamp.

After 20 minutes, we peel off the boot-pack trail and end up just above a snow-covered cliffband. Rocks and trees poke out at odd angles. Wind lips have created a row of vertical fingers. It’s like a miniature Alaskan face. “Think we can ski this?” Pam asks. “Just hike up your skirt, sister, and ski it,” I tell her. There’s really no other way down. I make four hop turns down one of the fingers. Stopping midway, my skis scrape the finger walls. Four more ungainly turns and we’re down.

Max promises the rest will be cake. “Not much to worry about in here; just point ‘em,” he says. So we bound through the moss-covered trees, through a foot of untracked over big rollers, picking up speed. Suddenly the earth drops away and I’m flying. Mystery air. I drop eight feet to a pillow–which I actually land–then another 10 to the slope below, where I stick the landing with my rump. I look back up, with no small amount of shock, at a gargantuan boulder. Max peers over the edge from above, “Whoah! Huckin’ Helen! Right on!!” Then he backs up and launches the whole thing.

Hucking gives you an appetite, so we head for Red’s base lodge. Like the lift system and the snow-grooming fleet, the lodge is refreshingly underdeveloped. When it was built in 1947, the area was owned by a ski club, and the lodge was a sort of clubhouse. Skiers could rent a cot for the night for a buck. In 1989, the club sold the mountain to Skat Petersen, but he hasn’t changed much. Later, when Pam and I have dinner with Skat at the Uplander in town, he tells us of his plans for a 100-room, four-star hotel with hot springs at the base. But today, most skiers have brought sandwiches from home and Tupperware filled with leftovers. The cafeteria is packed with kids—school groups imported by bus. “They’re breeding a hockey team,” Pam decides. We head upstairs to Rafter’s and devour a pizza.

Over lunch Max introduces us to a few of the local hot shots. There’s Kirsty Exner, Red’s 22-year-old extreme darling and the antithesis of a Telluride trustafarian. Her dad is a welder who works at Rossland’s zinc and lead smelter. “Big smoke brought the work,” she says. Ski tourism brings in some cash, but the region’s main industry is the smelter. And there’s World Cup downhiller Kevin Wert, 22, a big guy with a shaved head and blond goatee just back from Nagano. He tells a similar story: His dad, who puts up poles for West Kootenay Power, would drop him off at Red at eight in the morning and pick him up some 14 hours later. “In Rossland, you either ski or play hockey; there’s nothin’ else to do,” says Kevin. We make plans to meet them in the morning.

The fog is so thick that snow and sky blend into one horizonless gray slate. “Just tuck it,” Kevin advises and takes off into the soup. Those with vertigo do not tuck, Pam insists. Instead, we seek definition in the trees. Kirsty leads us to what she calls Orgasma. At this point Max, Kirsty, and Kevin begin arguing over trail names. What she calls Orgasma, Kevin calls The Needles. What he calls The Needles, Max calls Cambodia, and so on. Basically the trail map at Red is useless. For starters, Granite’s cone doesn’t translate well onto a two-dimensional piece of paper. The map indicates 75 marked runs, but on the mountain, only the groomers have trail signs.

Whatever it’s called, the run is a series of 45-degree steeps, narrow chutes filled with deep snow, trees, and big rocks. Wind lips form minichutes within megachutes. “This looks a little gnarly,” I say to Pam, who tells me to hike up my own skirt. We pick our way down, making hop turns, emergency stops, and dropoff-hop maneuvers. Kevin clips a tree and says, “Either those trees got tighter since I was a kid, or I got bigger.” This, of course, inspires remarks about the size of his downhiller butt. Below, the run opens up into a powder field, then flattens out onto a boulder field. We porpoise our way down, exploding the gigantic mushrooms of snow.

Day three: A fog that would make San Fran look clear means we still haven’t seen the mountain. Pam is preparing for more vertigo. But about halfway up Granite, the chair rises out of a sea of clouds. It is crystalline on top. We can see beautiful steeps and glades and chutes. Giant snow ghosts stand guard over the “Coolers” (Redspeak for couloir) at the tip-top. In the distance, the Valhalla and Bonnington Ranges poke through the clouds. I couldn’t have dreamed up such a spectacular sight.

And at the end of another day of never skiing the same line twice, I’m grinning. Pam tells me I’ve got a little something stuck in my front teeth. It’s moss.

The next stop on our tour is Fernie, a five-hour drive to the east. The first day, we treat ourselves to cat skiing at Island Lake Lodge. The morning dawns blue. This seems unusual. The cat is filled with an odd assortment, including our guide, Reto, a bushy-bearded Swiss who smokes a pipe while skiing; Bob, Rob, and Ben Mullin, on their annual boys’ trip; and a gonzo older guy and his reluctant girlfriend.

We ride the cat up toward a triumvirate of limestone peaks called the Three Bears. They look like mini-Matterhorns. Island Lake owns 7,000 acres of bowls and trees and chutes, and three 12-person snowcats. Roughly 200 acres a skier.

On a run called Breathless, we find creamy but heavy snow on a 38-degree pitch dappled with tiny fir trees. These turns are floaty, but lower down the sun has baked the snow to a perfect crème brûlée mush underneath a crusty layer that explodes off my shins in great chunks.

After a few runs, Reto decides, “You know what? I’m not doing the normal guiding anymore.” Our Rastafarian cat driver, Chris, grins knowingly and takes us to 45 Nonstop. The cat plows the trail up; no one has been up here in a while. A good omen. Chris drops us off on a saddle surrounded by jaggy peaks. Snow sloughs cascade down the rocks. We shoulder our skis and hike up a knife-edge just wide enough for a small pair of boots. “Didn’t think you’d be hiking on a cat-skiing trip, did you?” Reto ribs us. But we don’t mind. One at a time, we each make several dozen turns down a winding gully framed by dizzyingly high rock walls (mama bear and papa bear). The snow is light, deep and untracked.

After six runs, at nearly 2,000 verts a run, we head back to Island Lake’s cozy lodge. We drink big bottles of Fischer Hoopla amber ale in front of a huge stone fireplace. After dinner and too much red wine, Pam and I hitch a snowmobile lift back to Fernie from a nice young man with a bull ring in his nose. Around the first bend, the sled tips over and we all fall off. He tells us to keep our legs tucked in, just in case we fall again. What are the chances? I think to myself. The ride down is spectacular. We race through the woods, cold air biting our faces, a full moon lighting the peaks brighter than day. It is magic. Until we tip over and fall off again.

Fernie Alpine Resort is another magical place where temperatures are mild and snowfalls massive. They call it the Fernie Factor: Arctic air tumbles down from the north and collides with moist Pacific air masses, unloading mighty amounts of snow. And with three valleys converging at Fernie, the storm systems often get jammed in for days. The ski area is a series of bowls, stacked like a row of tilted teacups along a granite shelf, the massive cliff walls and craggy peaks of the Lizard Range. The bowl skiing is wide-open and mellow. Pam and I ski mostly in the steep, gladed ridges in between, where there’s enough pitch to blast through the wet spring slush.

Fernie’s layout is deceiving. Since arriving, we’d been eyeing the area’s front face runs–Sky Dive, Stag Leap, and Decline–three narrow paths cut through thick spruce and Douglas fir. But they can only be accessed by riding two chairs, a T-bar, then traversing the bowl and hiking to the ridgetop.

That face and the rest of Fernie make for a spectacular backdrop to town. Like Rossland, Fernie is home to the workingman. Coal was discovered a century ago, and today the economy remains based mostly on lumber and coal mining, and to a degree, ski tourism. Which is why I end up skiing with a coal miner.

Darrell Schmidt, a blue-eyed, gray-haired 48-year-old with deep laugh lines, is a welder at one of Fernie’s mines. His four-days-on, four-days-off schedule means he skis a lot. He wears heavily duct-taped ski pants and a layering system of cotton on cotton. We pass two snow guns. “That’s the extent of our snowmaking,” says Darrell. Last season, he tells me, it snowed 39 feet¿18 consecutive days of fresh in December alone.

There aren’t any high-speed quads, either. Lots of slow-moving chairs, T-bars, and of course, the Face Lift. Darrell calls it the Lift From Hell. The top of Lizard Bowl is so avalanche-prone that this towerless lift is the only kind that can survive. It’s basically two bullwheels and a long thin cable with evenly spaced meat hooks. And you’re a slab of beef getting dragged up a mountain by the backs of your legs. The snow is a glutinous gumbo that’s impossible to turn in. My ACLs insist we start skiing groomers.

But Fernie is a ski area on the edge of change. Relatively unknown in the lower 48, this powder paradise was snatched up by Canadian Charlie Locke in 1997. Now he owns seven B.C. ski areas, including Lake Louise, and has big plans for Fernie. By ‘98-’99, he will have poured C$8 million into lifts (including a high-speed quad for January ‘99), trails, and base facilities.

Pam and I have made reservations to go cat skiing in the expansion area, but the weather has gotten too warm, the snow too slushy. Still, we make friends with the cat drivers, Carl and Trent, and they take us up on snowmobiles so we can have a look. (By now I have developed a tremendous fear of tipping over.) We switchback up the cat road into Timber Bowl, the second teacup over from Lizard, where the two new chairs will go in. They’ll double Fernie’s terrain, accessing three new bowls: Timber, Currie, and Siberia. Beyond Siberia, for those willing to hike, is Mongolia Bowl, then Outer Mongolia…. Sounds like a little place called Vail.

Fish Bowl is the teacup to the north of Cedar Bowl, and that’s where Jack McKay takes us. A former used-car salesman from Calgary, he’s been skiing Fernie since 1974. This makes him a Calgaferniean. Five years ago, he moved to Fernie for good. “I still haven’t grown up yet,” he tells us. “I’m a 43-year-old ski bum.” Tanned and fit, he looks sort of like a baked Bob Beattie.

We have to duck a rope to get to Fish Bowl, but Jack assures us it’s okay. We traverse out to an area rippled with small gullies and sprinkled with alder bushes. It’s so steep, my hip hits the slope a half dozen times, and snow sloughs around my feet like quicksand.

Pam makes careful turns, alternating between gully and ridgeline. “You girls are fun,” Jack says, surprised that we’ve been able to keep up. “I took a couple of business guys back here last week and they almost died.”

It’s Saturday, and there are maybe five-minute lines at the Bear T-Bar. Jack apologizes. We ski what he calls 44, a short 44-degree pitch littered with alder. As we arc through the soft snow, we are startled by a shrill gobble-gobble coming from the trees. It’s a guy with a vintage fur-trimmed leather coat (“the latest from The North Face,” he says) and his friend, who’s wearing bright orange pants and striped jacket circa 1973, both two sizes too small. They’re sitting in the trees drinking beers and gobbling at people.

Later we ski Steep and Deep, a fall-line plunge at the end of Snake Ridge. It’s covered with the thickest glop I’ve ever encountered. Jack calls it elephant snot. The snow sprays from our skis in liquid streams. Pam and I figure it’s beer o’clock, but the boys insist we ski Skydive first. Like Alta’s High Rustler, Skydive is an endless vertical run situated in full view of the lodge. The snow is the consistency of warm peanut butter, but the pitch is steep enough that we can blast through it. A second wind carries us to the bottom, but only that far. We’re done. In the bar I give Pam 20 bucks U.S. to buy us a couple beers. She comes back grinning with two beers and, thanks to the exchange rate, 20 loonies in change.

Before bed tonight, I will think about this and about snow ghosts and mystery air and fresh tracks and hanging moss and mini-Matterhorns. And I will try to make my dreams half as good.

This article, which won a Northern Lights Tourism Award in 1999, first appeared in Skiing Magazine, March 1999