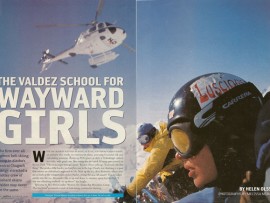

Ladycation: Alaska Heli-Skiing

outdoor writer for magazines, newspapers, and books

Cooling off in one of dozens of waterfalls along the Niobrara.

The author and kids on the banks of Merritt Reservoir.

Helen Olsson is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Boulder, Colorado. She is the author of The Down and Dirty Guide to Camping with Kids. Read More…

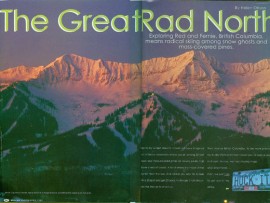

Exploring Red and Fernie, British Columbia means radical skiing among snow ghosts and moss-covered pines. […]

View Article

Any mom will tell you it’s hell just mobilizing a trip to the grocery store […]

View Article

Backpacking Near Silverton, CO, with Four-Footed Friends It was a sublime moment. Deep in the […]

View ArticleCopyright © 2026 on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in